On Strangers and Loneliness

“Familiar Strangers form a border zone between people we know and the completely unknown strangers we encounter once and never see again. While we are bound to the people we know by a circle of social reciprocity, no such bond exists between us and complete strangers. Familiar Strangers buffer the middle ground between these two relationships. Because we encounter them regularly in familiar settings, they establish our connection to individual places.”

-Eric Paulos and Elizabeth Goodman, “The Familiar Stranger”

In current times, we are constricted to our small surroundings, what we know and are comfortable with. These intimate settings have helped us foster deeper relationships with, and better understandings of, those closest to us. However, what happens to the people we know, but who we have never interacted with?

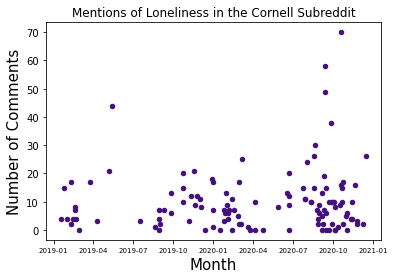

We often refer to loneliness, the subjective feeling of having inadequate social connections, as an unfortunate epidemic. We see this especially during the timeline of COVID. To look at how loneliness sentiment on Cornell’s campus this year, we can look to the platform where students can anonymously vent their frustrations and look for anonymous confirmation—the Cornell subreddit.

On top of piles of work, we add in social isolation and working remotely, so it is unsurprising that mentions of loneliness are most clustered during school months. Moreover, we have seen an increase in mentions of loneliness and comments on these posts in 2020 compared to the previous year. Part of this can be stemmed back to the fact that we now lack common spaces to sporadically encounter friends, strangers, or familiar strangers.

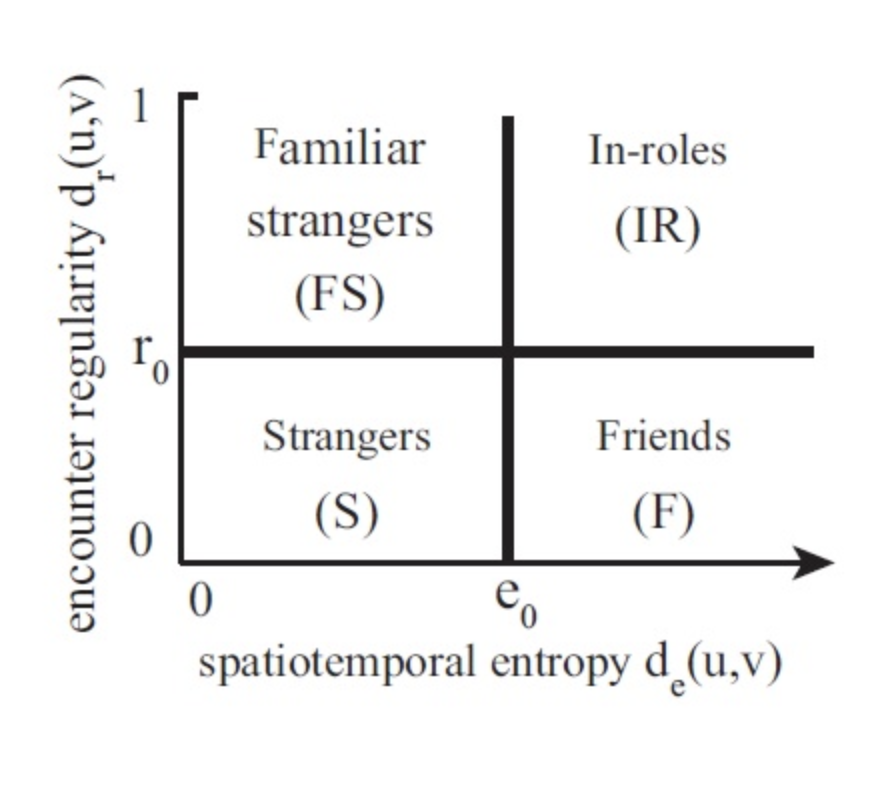

Researchers at Fudan University classified human relationships on college campuses into the four categories shown in the figure above: in-roles (which includes colleagues, classmates, and others who we are acquainted with and see on a regular basis), friends (those who we are acquainted with, but do not see regularly), strangers (those who we are neither acquainted with nor see regularly), and familiar strangers (those who we see regularly during our regular activities, but are not acquainted with - take, for example, the barista at your favorite cafe or the person that shows up to study at the library at the same time as you every Friday). By analyzing Wi-Fi and dining hall data sets on college campuses, they found that strangers, unsurprisingly, made up the largest chunk of instances where two people were at the same place at the same time. Familiar Strangers were the second largest.

While these encounters with strangers are random, encounters with Familiar Strangers are not. We recognize them and look for them when we go to these places or engage in a certain activity. A study conducted by Eric Paulos and Elizabeth Goodman found that people were most comfortable going about their daily routines when there were more familiar people nearby, as they wanted assurances of reliability from those around them. They also found that the further we are from our routine encounter with a Familiar Stranger, the more likely we are to establish direct contact, like starting a conversation. Take, for example, a new class or organization, which would offer a semblance of comfort and familiarity and help us feel less isolated in strange environments. Our Familiar Strangers are not something we seem to actively miss during these times, but they provide more meaning to our life than we immediately think. They are our connection into the completely unknown and help make us feel a tiny bit less lonely.